The Dawnland

The First Nations in the Dawnland

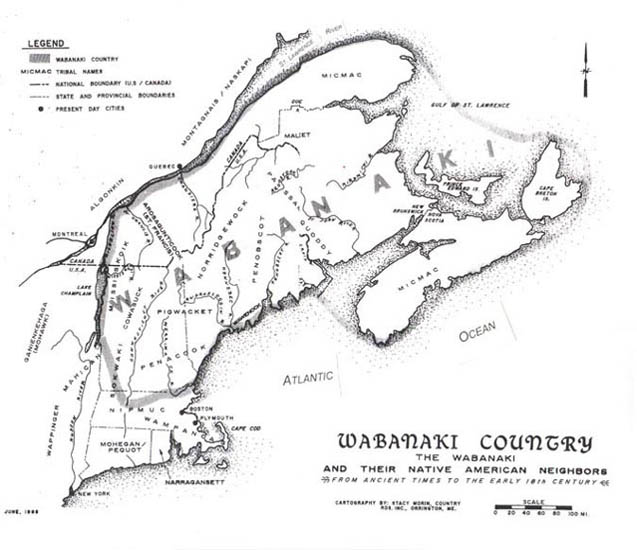

The traditional homeland of the Abenaki is Wobanakik ("Place of the Dawn"), what is now called Northern New England and Southern Quebec. The St Francis/Sokoki Band with other bands, including the Pennacook, Winnipesaukee, Pigwacket, and Cowasuck, comprise the Western Abenaki (Vermont and New Hampshire), while the Eastern Abenaki, including the Penobscot, Androscoggin, Wawenock and Passamaquoddy, reside in Maine. Abenaki also live in Quebec, with sizable communities at Okanak and Wolinak (Becancour). Both Eastern and Western Abenaki belong to the Wabenaki Confederation along with the neighboring Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Micmac and Mamiseet bands of Maine and the Maritimes area. All are part of the Algonquian-speaking linguistic family that includes Native peoples in the Northeastern United States and Eastern-central Canada. The regional influence of these nations is mapped above (cartography by Stacy Morin).

The Wabanaki treaties in the 17th and 18th centuries involved the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Nations. The signers of the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth were identified as members of the Penobscot, Kennebec and St. John's River groups and this website focuses on those Nations.

This essay by Dr. Harald Prins, posted to the Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point ME Tribal Government website, offers a short overview of the origins of the Wabanaki Confederacy, how the struggle between England and France impinged upon the native peoples and how they attempted to resolve the challenge to their homelands through diplomacy, from the first Anglo-Wabanki War (1675-78) through Dummer's Treaty of 1727.

The Wabanaki -- "people of the first light" -- lived in the Dawnland, on the northeast coast.

Background

There are several museums dedicated to the history and culture of these tribes in New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont and Quebec. These museums work in partnership with the indigenous descendants of those who lived in the Dawnland at the time of the Treaty of 1713, and offer these links to more information about the individual tribes.

In Maine, the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor commemorates and celebrates the traditions of these groups:

Passamaquoddy: Indian Township

More information about the Wabanaki is also found in Quebec at the site of the outpost that attracted many refugees:

Understanding the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth also provides insight into contemporary issues, including the UN Declaration of Rights of Indigenous People. (http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf)

First Nations Diplomacy in the Dawnland

“When we heard it was Peace between England and France we were very glad and hoped wee should soon have a Peace here. If the Queen at home makes this Peace contained in those Articles as Strong and durable as the Earth Wee for our Parts shall endeavour to make it as strong and fi rm here.” The English explained that “the Queen of Great Britain’s Arms were superior to those of the King of France and he had surrendered up Newfoundland and the Land on this side.” The members of the First Nations replied “The French never said anything to us about it and wee wonder how they would give it away without asking us, God having at fi rst placed us there and They having nothing to do to give it away.” -- Wabanaki speaker at Casco Bay, July 18, 1713

When the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 brought a halt to war between the French and English, it brought a new balance of power to northern New England that affected the daily lives of the First Nations inhabitants of the seacoast, their French allies and the English settlers on the frontier in Portsmouth. The negotiations in Portsmouth with the English colonial governor intended to define the terms of the peace between the First Nations and the Boston-based colonial government of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine. The Treaty of 1713 was one of several treaties the Wabanaki (the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Nations) entered into with different European groups that created new relationships in the far Northeast.

A close reading of the record of these negotiations in Portsmouth and Casco Bay offers an example of the distinction historians make in the styles of diplomacy in the Dawnland. Micah Pawling, University of Maine at Orono explains the accepted view that, “While European officials focused on the written products in their diplomatic interactions with the First Nations, Wabanaki leaders emphasized the collaborative process of treaty making, including council meetings, where indigenous delegates relied on the spoken word to protect aboriginal rights and secure favorable relationships for their communities.”

JULY 1713

The meeting at The Castle in July 1713 was not the first between Governor Dudley and representatives of the First Nations. At their July meeting, Dudley chided the sagamores for breaking five previous treaties -- made in 1687 with the Royal Governor of New York, in 1699 with Massachusetts Royal Governor Phipps, in 1700 with Govenor Bellomont and in 1702 and 1703 with Dudley himself. War had continued with attacks by the English on Norridgewock (1705) and by the allied French and Wabanaki forces on the Portsmouth Plains (1696), Wells (1703), Exeter and Dover (1706) and Saco (1710).

The English agreed to meet on the frontier in what is now Portsmouth, New Hampshire with First Nations representatives from the Penobscot, Saco, Kennebec and St. John’s river areas around Casco Bay to discuss their points of conflict. At the July 11-14, 1713 conference English and representatives of the First Nations signed a document they then presented to a gathering of the tribes at Casco Bay on July 17-18, 1713, as council meeting diplomacy dictated.

While the English began including the language of submission, to show English hegemony in the New World, with the 1693 Treaty of Pemaquid; Jesuit missionary Sebastien Rasles commented about the Wabanakis, ""There is not one savage Tribe that will patiently endure to be regarded as under subjection to any Power whatsoever; it will perhaps call itself an ally, but nothing more." Rasles was same same French missionary who reported that at the Casco Bay meeting where the 1713 Treaty terms were presented, one Wabanaki speaker said, “I have my land that I have not given, and will not be giving, to anyone. I wish always to be the master of it. I know its extent and when anyone wishes to come and live there, he will pay." The First Nations spoke from a position of strength.

Both sides understood the Treaty sought to manage a complicated balance on the northern New England frontier. The Wabanaki sought three things: trustworthy trading partners in more coveniently located "truck houses," diplomatic protocols including the exchange of gifts of tribute and the limitation of English expansion so that the tribes could preserve their culture on the seasonal hunting, fishing and planting grounds. Royal Governor Dudley sought proof he could give the Queen (and his own settlers) that England was in firm control of the disputed land and that French-Wabanaki alliances were being subdued. He also recognized the most important need on the ground in New England was to make the killing stop. Both sides accepted the written Treaty as a symbol of friendship. The 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth was also the first that identified "New Hampshire Councillors," making it the first step on a road that would eventually lead to recognition of New Hampshire as a colony, separate from Massachusetts/Maine. After 1713, and while Dudley practiced the double diplomacy that was the pragmatic answer for the Crown, for the colonies and for the Wabanaki, peace brought prosperity to Portsmouth.